Readable code#

The principles outlined in this chapter represent good practices for general programming and software development. These have been tailored to analytical workflows.

Pre-requisites

To get the most benefit from this section, you should have an understanding of modular code, which was covered in the previous chapter. You should also be familiar with core programming concepts such as:

storing information in variables.

using control flow, such as if-statements and for-loops.

You can find links to relevant training in the Learning resources section of the book.

Motivation#

Code is read more often than it is written.

—Guido van Rossum (creator of Python)

When writing code, we should expect that at some point someone else will need to understand, use, and adapt it. That someone might be you in six months time! As such, it is important to empathise with these potential users and write code that is tidy, understandable, and does not add unnecessary complexity. Doing this will make for a ‘self-documenting’ codebase that does not need as much additional documentation.

This chapter highlights good coding practices that will improve the readability and maintainability of your code. Here, readability refers to how easily another analyst can gain a decent understand of how your code works, within a reasonable amount of time. Maintainability refers to how easily other analysts can understand your code well enough to modify and repair it.

Clean code#

Programs are meant to be read by humans and only incidentally for computers to execute.

—Donald Knuth, The Art of Computer Programming

Code with high readability is often referred to as ‘clean code’. Clean code helps us understand a program faster, as it avoids points of confusion and ambiguity.

The following sections set out some key aspects of writing clean code that are fairly widely applicable. That said, each individual programming language has idiomatic ways of writing code that are specific to its features. Additionally, each language usually has some form of accepted style guide.

Make sure to consult the style guides for your language as first point of call. It is important to stress this point, as these guides will capture the most up to date guidance for your language of choice, which may not be available in this document.

Use informative names#

The most important aspect of clean code is the naming of identifiers within your code. This includes variables, functions, classes, constants and any other objects that can be assigned a name.

Someone reading your code will benefit greatly if you use names that are:

informative and not misleading.

concise but not cryptic.

Give variables clear and concise names#

You may have previously come across code that contains variable names that are meaningless, or that imply an incorrect purpose:

import pandas as pd

x = "Sioban"

y = 42

z = pd.DataFrame()

my_favourite_number = "ssh, I'm a string"

x <- "Sioban"

y <- 42

z <- data.frame()

my_favourite_number <- "ssh, I'm a string"

Another developer, or even ‘future you’, would be unable to correctly interpret what these variable names to represent. Therefore, you should try very hard to avoid cryptic or single-letter identifiers.

That said, there are situations where some seemingly cryptic identifiers make sense. Using single letters to name variables is suitable when implementing methodologies from mathematical notation. However, even in these cases you must make sure that the formulas being implemented are clear, readily available to the reader and are consistent throughout your code. Be sure to cite the source of the mathematical formula in these cases.

In other cases, using variable names that contain a few (3 or so) informative words can drastically improve the readability of your code.

Your language of choice will impact how you separate words (be it CamelCase or snake_case).

import pandas as pd

# Defining variables

first_name = "Sioban"

number_of_attendees = 42

empty_dataframe = pd.DataFrame()

# Using variables

print("Hi " + first_name)

number_of_attendees += 1

empty_dataframe.empty

# Defining variables

first_name <- "Sioban"

number_of_attendees <- 42

empty_dataframe <- data.frame()

# Using variables

paste("Hi", first_name)

number_of_attendees <- number_of_attendees + 1

plyr::empty(empty_dataframe)

Ideally, the purpose of variables should be clear from reading their names. In addition, the variable names should make logical sense in the context that they are used later on in the code. This removes the need for explanatory comments, as your intentions can be interpreted from the code itself (‘self-documenting’ code).

Naming is important for distinguishing between similar variables. A first instinct might be to assign numerical suffixes or other similar tags to differentiate variables. However, unless the suffix itself is meaningful within the context of the rest of the code, it will not make the code more understandable:

letters_1 = ["a", "b", "c"]

letters_2 = ["x", "y", "z"]

letters_1 <- c("a", "b", "c")

letters_2 <- c("x", "y", "z")

Here we can infer what these lists and vectors contain, but it is not apparent what makes letters_1 different to letters_2.

Variable names can be used to document differences between variables, or to incrementally describe changes made to a variable.

letters_first_three = ["a", "b", "c"]

letters_last_three = ["x", "y", "z"]

letters_first_three_reversed = reversed(letters_first_three)

letters_first_three <- c("a", "b", "c")

letters_last_three <- c("x", "y", "z")

letters_first_three_reversed <- rev(letters_first_three)

Here the naming convention indicates that both lists are similar, but also describes the differences between them. It is also clear how the third, new list relates to the first list that was used to create it.

With more informative names, we obviously lose the brevity of variable names:

letters_first_three_reversed_plus_t_minus_a_converted_to_greek

There is a clear trade-off between the usability and informativeness of variable names. You’ll need to use your best judgement to adapt variable names in order to keep them informative but reasonably concise.

Note

You will be more aware of this trade-off in languages like Python, where indentation is part of the syntax to denote code blocks.

The PEP8 style guide for Python recommends line widths of 79 characters. Having overly descriptive names might impact your compliance with a style guide.

Name functions after the task that they perform#

You should respect the best practices already covered in the Naming variables when naming functions. However, there are a few other points worth raising that are exclusive to function and method names.

Firstly, your user should be able to infer the purpose or action of a function from its name. A warning sign that your function may be overly complex or require further detail in its documentation is when you find that you can’t describe the overall task performed by the function in a few words.

It can be effective to describe the specific task a function performs in its name, starting with a verb:

def process_text(data):

...

processed_text = process_text("The following document was handled using...")

process_text <- function(data) {

...

}

processed_text <- process_text("The following document was handled using...")

This is often a tidy way to structure high-level functions in your pipeline. Well defined, verb-based names often lead to clear pipelines such as:

data_path = "path/to/data"

# in short

report_data = generate_report( model( clean( load( data_path ))))

# or, more explicitly

data = load(data_path)

clean_data = clean(data)

model_results = model(clean_data)

report_data = generate_report(model_results)

data_path <- "path/to/data"

# in short

report_data <- generate_report(model(clean(load(data_path))))

# or, more explicitly

data <- load(data_path)

clean_data <- clean(data)

model_results <- model(clean_data)

report_data <- generate_report(model_results)

Naming a function in the form of a question is useful when in cases where a function responds with a Boolean (True or False) value.

def are_missing_values_present(data):

if None in data:

return True

else:

return False

are_missing_values_present <- function(data) {

if (NA %in% data) {

TRUE

} else {

FALSE

}

}

This improves the readability of code that applies these functions.

if is_clean(data):

model(data)

if (is_clean(data)) {

model(data)

}

Make classes easy to identify#

Class names are usually started with a capital letter, and in CamelCase, as this differentiates them from variableNames and variable_names.

Class names follow the same advice as for Name functions after the task that they perform - namely, is it obvious from the class name what it does?

If it is too complex to name concisely, it is an indication of too many responsibilities

and you should refactor your code into more, smaller classes.

Method names in a class closely follow the requirements for Name functions after the task that they perform, as methods are just functions that are tied to a class.

They should ideally read clearly when called from a class instance - such as bookParser = TextParser(book_data) followed with bookParser.getNextWord().

Compare this against bp = Reader(book_data) then bp.fetch(), where there is not enough context.

Note

Writing custom classes is more common in Python than in R, as discussed in the Modular code chapter. As such, the examples above only apply to Python.

Make code easier to read by following a consistent style#

Programming languages can differ in lots of ways. One way R and Python differ, for example, is their use of indentation. Indentation is part of the well defined syntax of Python but is not for R. This does not mean that you shouldn’t use indentation in R to make your code more readable. If in doubt, you should consider consulting how to use formatting to write more readable code by finding the style guidelines for your language.

Generally, code style guides provide a standard or convention for formatting and laying out your code. The purpose of these style guides is to increase consistency across the programming community for a given language.

They might include how to appropriately:

comment or document your code.

name your functions, variables or classes.

separate elements of your code with whitespace.

use indentation to make sure your code is readable.

provide other useful guidance regarding formatting.

The existence of such style guides does not necessarily mean that each individual or team will apply these conventions to the letter. Organisations and developer teams often have needs that might not be addressed in a general style guidance document. After all, these documents aim to capture the needs of a diverse group of developers. Therefore, these guides are more useful as starting points in a discussion on ‘how should our team be consistent internally in the way we write code?’.

The core idea around these guides is that individual teams have to either adopt them or adapt them for use while writing code. The goals are readability and consistency. This consistency between developers will most likely aid speed of development and review, as well as the ability of one developer to comprehend code written by their colleagues.

Common Style Guides

PEP8 is an official Python style guide, which is widely used. The Google and tidyverse style guides are commonly used for R.

Write code that other programmers will find easy to read#

There is perhaps a misconception that following style guidelines and formatting your code accordingly is the fundamental goal of writing good code in a given language.

In reality, guidelines may encourage code-reviews to focus on style over more fundamental problems with the code. They have the potential to detract from assessment of whether the code is making the best use of a given language.

The notion of style goes beyond simple spacing or capitalisation. In the same way that knowing and using common idioms such as ‘over the moon’ or ‘cold feet’ make you seem like a more fluent speaker of English, a part of being fluent in a programming language is being able to write ‘idiomatic’ code. Idiomatic stands for ‘using, containing, or denoting expressions that are natural to a native speaker’. In Python, idiomatic approaches to writing code are commonly referred to as ‘pythonic’.

This might mean simplifying complex and perhaps hard to read patterns into a simpler, but well established alternative. For example, the pieces of code below are equivalent:

# Example 1 - very unpythonic

i = 0

my_data = []

while i < 100:

my_data += [i * i / 356]

i += 1

# Example 2 - more use of Python features, such as `range` and `append`

my_data = []

for i in range(100):

my_data.append(i**2 / 356)

# Example 3 - making full use pythonic idioms, `range` with list comprehension

my_data = [i**2 / 356 for i in range(100)]

# Example 1 - not idiomatic

i = 0

my_data = c()

while (i < 100) {

my_data = c(my_data, i * i / 356)

i = i + 1

}

# Example 2 - more use of R features, e.g. `append` and idiomatic assignment (' <- ')

my_data = c()

for (i in 0:100) {

my_data <- append(my_data, i^2 / 365)

}

# Example 3 - making use of R's built-in vectors

my_data <- (0:100) ^ 2 / 365

The ability to write idiomatic code in a given language comes with time. However, it is important to think about it while looking at a given piece of code: is it using everything that language ‘X’ has to offer?

That said, we should still prefer readability over idioms that might make our code more complex. For example, attempting to fit too much logic into a single line of code can make it considerably harder to understand.

Automate style checks#

Following a style guide from the beginning of a project is good practice. However, checking that code continues to follow a particular style, or to fix code formatting when it doesn’t can be tedious. Hence, automated support can be sought to speed up this work, either by providing suggestions as the code is written or by reformatting your code to comply with some style.

See Linters and formatters for further information on automating these checks.

Software ideas for analysts#

It’s important to remember that when we write code for analysis, we are developing software. Over many years, software engineering teams have developed good practices for creating robust software. These practices help to make our code simple, readable, and easier to maintain. Analysts using code as a means to perform analysis can benefit from at least partially applying such practices in their own codebases.

This chapter will try to condense key messages and guidelines from these practices, for use by analysts who write code. Reading and learning more about these practices will likely to benefit the quality of your code and is highly encouraged.

Keep it simple#

The ability to convey information in a simple and clear way matters.

This is particularly true when explaining concepts that are already complex. You are often trying to solve problems that are complex in nature when writing code. You should avoid introducing extra complexity to these problems, wherever possible.

Here are a few tips to make sure you keep your project nice and simple:

Solve the problem - do not get distracted and make sure you have a clear outcome in mind.

Try not to ‘reinvent the wheel’ - use existing packages when they already have functionality that solves the problem. They will most likely be better documented and won’t need extra maintenance.

Split your code into understandable parts - consider how to make your code modular.

Don’t over-engineer your solution - if it is understandable and works, refrain from over-complicating for the sake of small increases in efficiency.

When you have a choice of alternative packages to do the same thing, use one and stick to it. For example, the R packages dplyr and sqldf both enable the use of selection and filtering operations. Stick to one unless there is a very good reason to use both. When choosing between alternatives, think about their familiarity for other coders, ease of use and efficiency.

Note

It’s important to capture the requirements of your code before writing it. This includes when your code needs to be adapted to meet changing needs. You should then aim to meet these requirements in the functionality that your code provides.

It can be tempting to try to account for every eventuality in your program, but developing anything more than these requirements may not be beneficial. There’s a good chance that many cases that you account for will never occur, so you should try to prioritise based on what you’re certain is needed from your code.

You ain’t gonna need it

Remember that additional features will require more documentation and testing to ensure that they are working correctly. Really consider if adding these extras will make your code more or less maintainable, user-friendly and correct.

Lastly, it is worth stressing that complex problems might require complex solutions. In those cases make sure that you only introduce complexity where it is needed. You should address necessary complexity with proportionate quality assurance - through documentation, testing and review. For instance, if the execution time of your code is critical, then making the code more complex to achieve a faster runtime may be an acceptable trade-off.

Don’t repeat yourself#

In the section on modular code, you were encouraged to refactor your code into more self-contained components for ease of testing, reproducibility and reusability. However, it is worth stressing that ‘quick and dirty’ solutions often involve copy-pasted code that is functionally identical. This is expected and is natural in the initial stages of a project. Nonetheless, repetition not only wastes your time, but it also makes your code more difficult to read. Consider a script that contains three copies of a similar piece of code. If the code that is used to perform the repetitive task is found to be incorrect, or if a developer wishes to modify the task being performed by this code, they must implement a similar change in each of the three copies. If only two copies were spotted and amended, there is now a bug sleeping in the code waiting to be triggered… Moreover, anyone reviewing the code would need to check that the right logic is being used three times over.

To put this in context, let us use an example where the developer wants to get the odd numbers from three different lists of numbers:

# Note: this is an example of bad practice

first_ten_numbers = list(range(1, 11))

second_ten_numbers = list(range(10, 21))

third_ten_numbers = list(range(20, 31))

odd_first = []

for number in first_ten_numbers:

if number % 2 == 1:

odd_first.append(number)

odd_second = []

for number in second_ten_numbers:

if number % 2 == 1:

odd_second.append(number)

odd_third = []

for number in third_ten_numbers:

if number % 2 == 0:

odd_third.append(number)

# Note: this is an example of bad practice

first_ten_numbers <- 1:10

second_ten_numbers <- 11:20

third_ten_numbers <- 21:30

odd_first <- c()

for (number in first_ten_numbers) {

if (number %% 2 == 1) {

odd_first <- c(odd_first, number)

}

}

odd_second = c()

for (number in second_ten_numbers) {

if (number %% 2 == 1) {

odd_second <- c(odd_second, number)

}

}

odd_third = c()

for (number in third_ten_numbers) {

if (number %% 2 == 0) {

odd_third <- c(odd_third, number)

}

}

In this example, the third repeated snippet of code actually collects even numbers, but incorrectly assigns them to the odd_third variable.

Because each copy looks very similar, you might assume that all copies of the code are performing the same task.

Even when you are aware of the difference between the copies, you might be unable to tell if the difference is intentional or a mistake.

The example demonstrates how repetition can add confusion when trying to maintain or review code.

Modifying multiple copies of a code snippet is laborious and presents a risk - some copies of the repeated code may be modified, while others erroneously remain the same. This is analogous to modifying the formula in individual cells of a spreadsheet. If you refactor repetitive code into functions or classes, then bug fixes or modifications need only be carried out once to change all uses of that code. New, intended behaviour is then consistently given by each call of the function or method.

The following presents how one could change the previous example for the better:

def get_odd(numbers):

"""Get only the odd numbers"""

return [number for number in numbers if number % 2 == 1]

first_ten_numbers = list(range(1, 11))

second_ten_numbers = list(range(20, 21))

third_ten_numbers = list(range(20, 21))

odd_first = get_odd(first_ten_numbers)

odd_second = get_odd(second_ten_numbers)

odd_third = get_odd(third_ten_numbers)

get_odd <- function(numbers) {

# Get only the odd numbers

numbers[numbers %% 2 == 1]

}

first_ten_numbers = 1:10

second_ten_numbers = 11:20

third_ten_numbers = 21:30

odd_first = get_odd(first_ten_numbers)

odd_second = get_odd(second_ten_numbers)

odd_third = get_odd(third_ten_numbers)

If the functionality of get_odd needs to be modified, it now need only be done once.

Additionally, this code is more concise and its purpose is easier to interpret.

Note

If two slightly different tasks must be carried out, for example you need both the odd and the even numbers, you might approach this in one of two ways:

Develop two functions containing the different elements of code, with names that express the difference in their purpose.

Add a parameter to your function that will allow a user to differentiate between the two tasks.

# Simple and modular

def is_odd(number):

"""Check if a number is odd."""

if number % 2 == 1:

return True

else:

return False

def get_odd(numbers):

"""Get only the odd numbers."""

return [number for number in numbers if is_odd(number)]

def get_even(numbers):

"""Get only the even numbers."""

return [number for number in numbers if is_odd(number) == False]

# More concise, but also more complex - not always best

def get_numbers_with_parity(numbers, parity):

"""Get numbers with a given parity ('odd' or 'even')."""

if parity not in ["odd", "even"]:

raise ValueError("parity must be 'odd' or 'even'")

remainder = 1 if parity == "odd" else 0:

return [number for number in numbers if number % 2 == remainder]

odd_numbers = get_numbers_with_parity(list(range(1, 11), "odd"))

# Simple and modular

is_odd <- function(numbers) {

ifelse(numbers %% 2 == 1, TRUE, FALSE)

}

get_odd <- function(numbers) {

numbers[is_odd(numbers)]

}

get_even <- function(numbers) {

numbers[!is_odd(numbers)]

}

# More concise, but also more complex - not always best

get_numbers_with_parity <- function(numbers, parity) {

numbers_with_parity <- c()

if (parity == "odd") {

remainder <- 1

} else if (parity == "even") {

remainder <- 0

} else {

stop("parity must be 'odd' or 'even'")

}

numbers[numbers %% 2 == remainder]

}

odd_numbers <- get_numbers_with_parity(1:10, "odd")

You should use your best judgement to decide which is most appropriate in a given situation.

It can be difficult to decide when repetition warrants refactoring of code into reusable functions or classes. The ‘Rule of Three’ suggests that if similar code has been written more than two times, then it is worth extracting its logic to a reproducible procedure like a function or class. However, as you write code you should try to anticipate whether it is likely to be reused in future. If the answer is yes, you might opt to write it straight into something more modular and reusable.

Be explicit#

In the literary sense of the word!

Explicit is better than implicit

—The Zen of Python (

import this)

In some programming languages, it is possible to perform a task or decision by relying on an implied interpretation of your code.

For example, in Python 1, 100, ["A list of text"] and many other objects evaluate to True, while 0, [] and None evaluate to False.

To make your intentions clear, you should explicitly state your intended comparison in the code.

student_count = None

# Relying on falseness of None

if student_count:

print("There are " + student_count + " students!")

student_count <- FALSE

# Relying on falseness of FALSE

if (student_count) {

paste("There are", student_count, "students!")

}

In the example above, the student count is not printed because None and FALSE evaluate to False.

In Python and R, 0 will also evaluate to False.

Therefore, it is unclear whether the programmer intended that the statement is printed when the count is 0.

If a count of 0 should be printed, then this lack of specificity has created a bug.

To perform the same decision explicitly, we should specify the exact condition under which the student count should be printed.

student_count = 0

# Explicitly print only if more than 0

if student_count >= 0:

print("There are " + student_count + " students!")

student_count <- 0

# Explicitly only print if more than 0

if (student_count >= 0) {

paste("There are", student_count, "students!")

}

Now the count is printed if it is more than or equal to 0. It’s clear that we intend for this to be the case.

Separate responsibilities#

An object should have a single responsibility. Only changes to one part of the software’s specification should be able to affect the specification of the class.

The ‘single responsibility’ principle suggests that a single element of your code (a function or class) should be responsible for a single part of your software’s functionality. It should take on one task and perform it well. This is because each piece of code is more robust if there are fewer reasons to change it in the future.

When you work with code that is designed to multitask, it is often difficult to modify this code without having an unintentional effect on other aspects of the software.

Imagine trying to create a model of the economy, which is a complex web of interconnected interactions. Creating ‘abstractions’ in the form of classes or functions that try to model multiple aspects of the economy at once might seem helpful, but when used incorrectly might instead add to the complexity.

For example, consider a class that represents a whole country (Country).

This would represent a model that is trying to predict economic statistics for a country such as unemployment or inflation.

One can imagine that this class will quickly grow into something unmanageable, as its responsibilities grow in the form of additional methods and attributes.

Based on the other chapters in this guidance, you might eventually realise that you need to break this class down further.

If you had applied the idea of single responsibility,

you might have broken the Country class down into smaller components such as UnemploymentModel, InflationModel.

These classes would be responsible for doing specific modelling, while the Country class might only responsible for presenting the results to,

let’s say, a higher level economy model that tries to model cross-country trade.

This simplicity also increases usability, by minimising the number of parameters that each function or class might require.

Note

If you remember the section on interfaces,

the different model classes here are a prime example where defining an interface would help you make sure each *Model object is interchangeable.

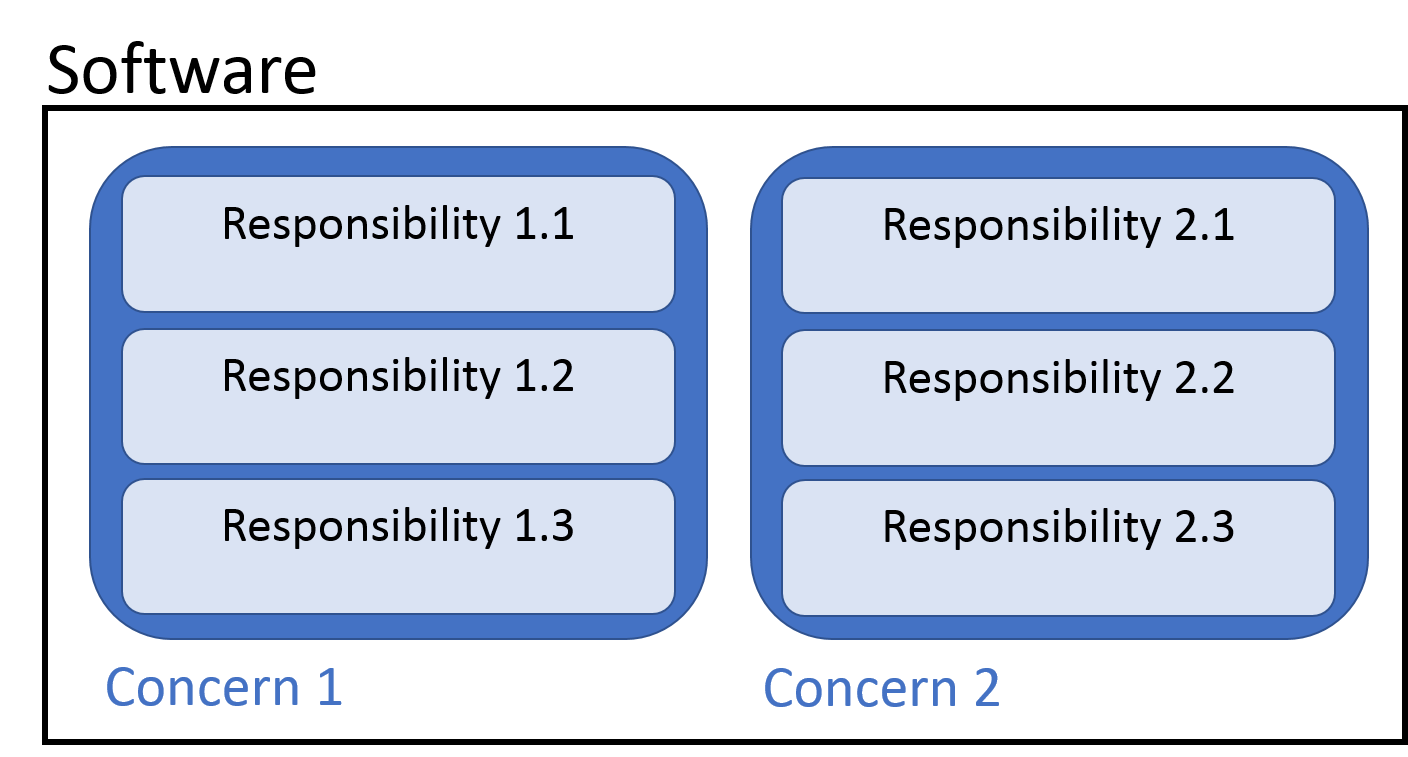

The ‘separation of concerns’ principle captures a similar concept to single responsibility, but on a higher level. This principle suggests that your software should be separated into distinct sections that each address a single concern.

In the previous economic modelling example, you might establish your concerns to be:

Model economy at low level:

UnemploymentModelandInflationModel.These are concerned with the ‘low-level’ details of giving estimates of economic output. They are independent of each other and concerned only by what they are trying to estimate.

Model country level interactions and trade blocks:

CountryandTradeBlock.These parts of your code relate to higher level concepts. They will be using the lower level

Modelclasses, but are primarily concerned with interactions between countries.Run simulations given a description of the desired economy.

Once the model is ready, there might be a

SimulationRunnerthat takes in your model of the world economy and runs simulations. In this case, this part of your codebase will only revolve around running the actual simulations.

In each of these distinct sections of your codebase there will be multiple classes and functions, which should follow the single responsibility concepts outlined earlier.

For example, within the section of your code concerned with modelling data, you might have a set of functions to download data from an external data store.

These functions should only be responsible for receiving the required data safely and providing it to the Model object.

If you had the need to download data from different sources online (i.e., Database, CSV or other), you might create several download functions.

To pick the right function for each model you might create a ‘LoaderFactory’

who’s only responsibility is to provide the Model with the right loading function for the right data source.

Fig. 3 Representation of concerns and responsibilities within a piece of software#

As such, separate sections of your software should be responsible for each of the concerns. Within each section of your software, distinct functions or classes should be responsible for each task that is required for that section’s overall functionality.

In the context of functions

The previous example was heavily focused on classes and Object-Oriented Programming. The same principles apply in the world of functions. You define each concern that is addressed by a module containing functions who follow the single responsibility principle.

So the previous example could equally include:

An

unemployment_model- function running the unemployment modelling.An

inflation_model- function running the inflation modelling.

These functions would produce data about a given country, to be stored in an object. Another function might then take these data for multiple countries and start modelling it across country boundaries.

The same core concepts still fully apply.

Make functions open to extension, but closed for modification#

This means that it should be possible to extend the functionality of classes or functions, without modifying their source code or how they work.

# some function that we want to keep closed for modification

def core_method(data):

...

return result

# if we want to extend a function without modifying it, we can always do the following

def extended_functionality(results):

...

return extended_result

def extended_methodology(data):

core_results = core_method(data)

return extended_functionality(core_results)

# some function that we want to keep closed for modification

core_method <- function(data) {

...

return(result)

}

# if we want to extend a function without modifying it, we can always do the following

extended_functionality <- function(result) {

...

return(extended_result)

}

extended_methodology <- function(data) {

core_results = core_method(data)

return(

extended_functionality(core_results)

)

}

The same applies to classes through ideas like inheritance.

When you think about the consequences of this, the open-closed principle gives you:

Confidence that essential behaviour of parts of your code should not be expected to change.

The ability to easily add more functionality, as your code evolves.

Note

In functional programming we use higher-order functions and functional composition to enact these principles. ‘Functional composition’ deserves a brief explanation, as a concept that might be keenly used in a data analytics pipeline.

In simple terms, functional composition is a mathematical idea that takes two functions \(f\) and \(g\) and produces function \(h\), such that \(h(x) = g(f(x))\).

Analysts familiar with R’s %>% operator will find this idea familiar.

Imagine you have a task to perform modelling and report generation from data. You can lay out your code to be easily composable with the following functions, with single responsibilities:

load- loads data.model- runs the model on data.report- runs report generation.

So when it comes to creating a pipeline you end up with something like:

report = report(model(load(filepath)))

report <- report(model(load(filepath)))

We will now assume that these individual functions are closed for modification.

However, we can extend the functionality of load by adding a clean function that cleans the data. In which case, we end up with:

# We can extend this without modifying the source code of `load`

report = report(model(clean(load(filepath))))

# or we can first define a new load as follows

def new_load(filepath):

return clean(load(filepath))

report = report(model(new_load(filepath)))

# or with the help of anonymous (lambda)

new_load = lambda data: clean(load(data))

report = report(model(new_load(filepath)))

# We can even use this to create a single function to run our defined pipeline

pipeline = lambda data: report(model(clean(load(filepath))))

report = pipeline(filepath)

# We can extend this without modifying the source code of `load`

report <- report(model(clean(load(filepath))))

# or we can first define a new load as follows

new_load <- function(filepath) clean(load(filepath))

report <- report(model(new_load(filepath)))

# We can even use this to create a single function to run our defined pipeline

pipeline <- function(data) report(model(clean(load(filepath))))

report = pipeline(filepath)