Data management#

Data management covers a broad range of disciplines, including organising, storing and maintaining data. Dedicated data architects and engineers typically handle data management. However, analysts are often expected to manage their own data or will work alongside other data professionals. This section aims to highlight good data management practices, so that you can either appreciate how your organisation handles its data or implement your own data management solutions.

We need to be able to identify and access the same data that our analysis used if we are to reproduce a piece of analysis . This requires suitable storage of data, with documentation and versioning of the data where it may change over time.

Key strategies

The Government Data Quality Framework focuses primarily on assessing and improving the quality of input data. It should be a primary resource for all analysts working with data in the public sector.

The Office for Statistics Regulation provides a standard for quality assurance of administrative data.

Data storage#

We assume that most data are now stored digitally.

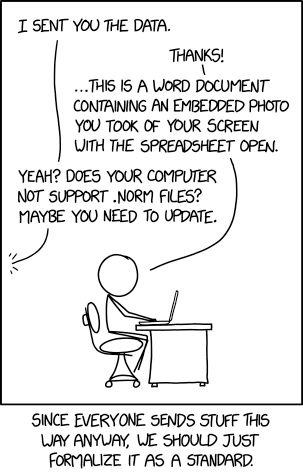

Digital data risk becoming inaccessible as technology develops and commonly used software changes. Use open or standard file formats, not proprietary ones, for long term data storage. There are recommended formats for storing different data types, though we suggest avoiding formats that depend on proprietary software like SPSS, STATA, and SAS.

Short term storage, for use in analysis, might use any format that is suitable for the analysis task. However, most analysis tools should support reading data directly from safe long term storage, including databases.

Spreadsheets#

Spreadsheets (e.g., Microsoft Excel formats and open equivalents) are a very general data analysis tool. The cost of their easy to use interface and flexibility is increased difficulty of quality assurance.

Do not use spreadsheets for storage of data (or statistics production and modelling processes). Using spreadsheets to store data introduces problems like these:

Lack of audibility - changes to data are not recorded.

Multiple users can’t work with a single spreadsheet file at once, or risk complex versioning clashes which can be hard to resolve.

They are error prone and have no built in quality assurance.

Large files become cumbersome.

There is a risk of automatic “correction” of grammar and data type, which silently corrupts your data.

Converting dates to a different datetime format.

Converting numbers or text that resemble dates to dates.

See the European Spreadsheet Risks Interest Group document spreadsheet related errors and their consequences for more information.

Databases#

Databases are collections of related data, which can be easily accessed and managed. Each database contains one or more tables, which hold data. Database creation and management is carried out using a database management system (DBMS). DBMSs usually support authorisation of access to the database and support multiple users to concurrently access the database. Popular open source DBMS include:

SQLite

MySQL

PostgreSQL

Redis

Relational databases are the most common form of database. Common keys (e.g., unique identifiers) link data in the tables of a relational database. This allows you to store data with minimal duplication within a table, but quickly collect related data when required. Relational DBMS are called RDBMS.

Most DBMS communicate with databases using structured query language (SQL).

Key Learning

You might find this foundations of SQL (government analysts only course) or w3schools SQL tutorials useful for learning the basics of SQL.

Common analysis tools can interface with databases using SQL packages, or those which provide an object-relational mapping (ORM). An ORM is non-SQL-based interface to connect to a database. They are often user-friendly, but may not support all of the functionality that SQL offers.

Key Learning

This guide covers Python SQL libraries in detail. While this Software Carpentry course covers SQL databases and R.

Other database concepts:

Schema - a blueprint that describes the field names and types for a table, including any other rules (constraints).

Query - a SQL command that creates, reads, updates or deletes data from a database.

View - a virtual table that provides a quick way to look at part of your database, defined by a stored query.

Indexes - data structures that can increase the speed of particular queries.

Good practices when working with databases include:

Use auto-generated primary keys, rather than composites of multiple fields.

Break your data into logical chunks (tables), to reduce redundancy in each table.

Lock tables that should not be modified.

Other resources:

This SQL lecture from Harvard’s computer science course may be a useful introduction to working with databases from Python.

A guide to using the

sqldfR package.

Documenting data#

It is difficult to understand and work with a new dataset without documentation.

For our analysis, we should be able to quickly grasp:

What data are available to us?

How were these data collected or generated?

How are these data represented?

Have these data been validated or manipulated?

How am I ethically and legally permitted to use the data?

Data providers and analysts should create this information in the form of documentation.

Data dictionary#

A data dictionary describes the contents and format of a dataset.

For variables in tabular datasets, you might document:

A short description of what each variable represents.

The frame of reference of the data.

Variable labels, if categorical.

Valid values or ranges, if numerical.

Representation of missing data.

Reference to the question, if survey data.

Reference to any related variables in the dataset.

If derived, detail how variables were obtained or calculated.

Any rules for use or processing of the data, set by the data owner.

See this detailed example - the National Workforce Data Set, from the NHS Data Model and Dictionary.

Please see UK Data Service guidance on documenting other data, including qualitative data.

Information Asset Register (IAR)#

An information asset register (IAR) documents the information assets within your organisation. Your department should have an IAR in place, to document its information assets. As an analyst, you might use the register to identify contacts for data required for your analyses.

Although this form of documentation may not contain detailed information on how to use each data source (provided by data dictionaries), an IAR does increase visibility of data flows. An IAR may include:

The owner of each dataset.

A high level description of the dataset.

The reason that your organisation holds the dataset.

How the information is stored and secured.

The risk of information being lost or compromised.

GOV.UK provides IAR templates that your department might use to structure their IAR.

Version control data#

To reproduce your analysis, you need to be able to identify the data that you used. Data change over time; Open data and other secondary data may be revised over time or cease to be available with no notice. You can’t rely on owners of data to provide historical versions of their data.

As an analyst, it is your responsibility to ensure you identify the exact data that you have used.

You should version and document all changes to the data that you use whether using a primary or secondary data source,. You should include the reason why the version has changed in documentation for data versions. For example, if an open data source has been recollected, revisions have been made to existing data, or part of the data has been removed.

You should be able to generate your analytical outputs reproducibly and, as such, treat them as disposable. If this is not the case, version outputs so that you can easily link them to the versioned input data and analysis code.

To automate the versioning of data, you might use the Python package DVC, which provides Git-like version control of data.

This tool can also relate the data version to the version of analysis code, further facilitating reproducibility.

You can use Git to version data, but you should be mindful of where your remote repository stores this data.

The daff package summarises changes in tabular data files, which can be integrated with Git to investigate changes to data.

You might alternatively version your data manually e.g., by creating new database tables or files for each new version of the data. It must be possible to recreated previous versions of the data, for reproducibility. As such, it is important that you name data file versions uniquely, for example, using incrementing numbers and/or date of collection. Additionally, do not modify file versions after they have been used for analysis - they should be treated as read-only. All modifications to the data should result in new versions.

Finally, for this to be effective, your analysis should record the version of data you used to generate a specified set of outputs. You might document this in analysis reports or automatically logged by your code.

Use these standards and guidance when publishing data#

You should use the 5-star open data standards to understand and improve the current utility of your published data. We recommend the CSV on the Web (CSVW) standard for achieving the highest ratings of open data.

When publishing statistics you should follow government guidance for releasing statistics in spreadsheets.

When publishing or sharing tabular data, you should follow the GOV.UK Tabular data standard.

Analysts producing published statistics may also be interested in Connected Open Government Statistics (COGS) and the review of government data linking methods.

The UK Data Service provides guidance on data security considerations.